Reflections on a Resident Art Practice in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside

By Savannah Walling

Published in

alt.theatre Vol 9.4 (June 2012)

Download a PDF of this article.

Over thirty-five years ago, Terry Hunter and I planted into the creative soil of the Downtown Eastside a seed that has grown into Vancouver Moving Theatre’s tree of community art practice.

Today this tree shelters and nourishes artists working with a community and a community working with artists in all kinds of collaborative relationships, giving birth to new art made with, for, and about the Downtown Eastside. The tree absorbs and sprouts from what is already in place: the neighbourhood’s diversity and accumulated wisdom. Its roots probe through multiple layers, cultural landscapes, and social systems, seeking understanding and connection. The tree’s branches weave individuals and groups into mutually beneficial relationships. Its trunk supports art-creation that celebrates, challenges, commemorates, educates, and heals. The tree grows through over-lapping phases of research and development, creation, and production before seeding legacies for the community, the next generation of artists, and other communities facing similar challenges.

Here is our story of the evolution of a Downtown Eastside tree of community art practice.

Looking for an affordable home in 1975, Terry and I moved into the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver’s founding neighbourhood situated on ancestral unceded Coast Salish territory between Burrard Inlet and the False Creek Flats. Here we discovered a diverse, largely low income community filled with people from different walks of life, circumstance, and culture. Before the Downtown Eastside was clear-cut one hundred and twenty-seven years ago, it was home to the tallest and oldest trees in Canada. Today the area is home to the largest urban Aboriginal unofficial “reserve” in Canada and the second largest historic Chinatown in North America: an entry point for immigrants and young families, a working and retirement home for resource workers, a haven for middle class professionals who value sustainability over growth, a sanctuary for artists and the marginalized, and site of major events in Vancouver’s history.

The Downtown Eastside has been a gathering place of vastly differing governance systems, cultural traditions, and art practices. Like a biologically diverse forest filled with “trees” of all kinds and sizes, the community’s diversity has been the source of its health, its fiercely productive creativity, and its divisive polarities—as well as its historic struggles and capacity for survival. In the words of Nathan Edelson, “The Downtown Eastside is a community that has experienced great suffering, but it is also a community that has demonstrated incredible resilience, determination, and innovation.”(1)

During our first years in the neighbourhood, Terry and I explored fusions of dance, music, and theatre within the avantgarde dance collective Terminal City Dance. By 1983 the company could no longer contain the expanding visions of its collective and it split apart into three entities: the Vancouver Dance Centre, Karen Jamieson Dance Company, and Vancouver Moving Theatre.

Terry and I co-founded Vancouver Moving Theatre (VMT) to house our inter-disciplinary art form, and to fulfill our dream of bridging barriers between cultures and connecting artistic practice with community. But it took fifteen years of touring drum dances and mask dramas before we stayed at home long enough for the dormant seed to sprout into six years of small-scale Strathcona Artist at Home Festivals (1998-2004). Through this festival we uncovered a rich vein of artists, history, cultures, and great stories. The more we learned and the more we participated, the more involved, inter-connected, and committed to our community we became. We began the slow journey of transforming from artists living in the Downtown Eastside to artists nurturing and being nurtured by this community.(2)

As we became connected to our community, our eyes opened to its beauty and the challenges stemming from poverty, self-reliance, and being treated as a dumping ground for the city’s problems. Over the years we’ve seen significant changes. A powerful partnership among developers, real estate investors, labour unions, and government has driven land development and rezoning, leveraging investment with mega-projects like Expo 86 and the 2010 Olympics. Insensitive development has threatened the community’s identity, human scale, and heritage, and has displaced residents. Policing actions in the 1970s that moved prostitution from indoors out onto the streets coincided with a series of murders and disappearances of sex trade workers. The traumatic legacy of Indian residential schools, the downsizing of mental hospitals, welfare rate reduction policies, privatizing and off-shoring of jobs, and the loss of affordable housing all correlated with a surge in visible poverty, survival sex trade and property crime, homelessness, and self-medicating on all levels of society. Furthermore, a new drive-by drug market spiralled out of control as Vancouver plugged into the global drug markets.

During the 1990s, new grassroots initiatives rose to lobby for systemic changes. Their goals were to make the neighbourhood a healthier place to live and to contribute through arts to restoring culture and transforming community. When residents engage in their community and culture, neighbourhoods start to heal and move forward. Vancouver finally opened a supervised drug injection facility—the first in North America. Artists, activists, and organizations participated in collective actions for community-led renewal during the one hundredth anniversary of the Carnegie Community Centre building at Hastings and Main.

The Carnegie Community Centre invited Vancouver Moving Theatre to co-produce a community play created for, with, and about the neighbourhood. Although the task was too big, timelines too short, and financial resources insufficient, we knew that our community, although negatively sensationalized by media across Canada, had tremendous talent. It was our turn to give back. Everyone involved hoped the project could bridge barriers of language, culture and social differences in a community experiencing serious threats to its survival.

Our community partner asked us to work with the community play principle discovered by British playwright Ann Jellicoe (1977). We agreed and visited Cathy Stubington and the community of Enderby to learn more about the process.(3) In this kind of community play, a small core of experienced theatre artists work with community volunteers—as many as wish to participate—to create artistic work that expresses and celebrates their community. Jellicoe had discovered an art-making process whose guiding principles replicate nature’s principles for building healthy eco-systems: diversity, interconnectivity, and interdependence.

Establishing a healthy root system is fundamental when organizing a diverse group of people to co-produce something that comes in on schedule and budget, navigates bumps, and is artistically coherent and meaningful. It took a month of negotiating with the Carnegie staff to agree upon the community play’s goals and guiding principles; expectations around social, cultural, gender diversity and bridge-building; and definitions of “Downtown Eastside,” “community member,” and “community play.”

The responsibilities were overwhelming for everyone involved.(4) As resident artists we couldn’t leave after the play was finished; we would have to live with the consequences and so would our community. We learned on the job. We asked for help. We learned about community values and traditional protocols. Undertaking the massive project was an act of trust by all involved.

The experience wasn’t perfect. All the challenges of producing big collaborative plays were present: from people who didn’t got along, got sick, weren’t prepared or didn’t understand English, to security issues, family emergencies, people with post-traumatic stress, robberies, computer crashes, evictions, mental health and drug issues, and aesthetic and cultural differences. But together we created an imperfect miracle. The audiences loved it. “A vibrant Downtown Eastside theatre community has been created,” said poet Sandy Cameron in the Carnegie Newsletter (1 Nov 2003). “People are getting to know each other. People connected to the play are greeting each other on the street. They know their play reflects the strength, pain and beauty of our multicultural Downtown Eastside that rises like a phoenix, from one generation to the other.”

Co-producing

In the Heart of a City: The Downtown Eastside Community Play (2003) turned out to be transformative for Terry, myself, and Vancouver Moving Theatre.. This was the moment when the creative seedling planted in the 1970s grew a deep and strong taproot, the foundation of our tree of community art practice. Guidelines inspired by Jellicoe’s play process and codeveloped with the Carnegie Community Centre have guided our evolving practice in the Downtown Eastside ever since.

When art projects end, the abrupt loss of daily rituals, social meetings, and meaningful work is rough on people in marginalized circumstances. After the community play ended, participants were hungry for more. Terry and I owed another big debt of gratitude. We had barely scratched the surface of the community’s stories. How ethical is it, we wondered, to do big community-engaged projects without sustaining follow-up and—in the words of Ruth Howard—“continuity or attentive wind-down”? What could we give back as thanks after the project was over? Whose responsibility was it? The artists? Community partner? Funding agencies? The community? The answer: All of the above.

The success of the community play stimulated new growth: an annual, massively inclusive creative opportunity. In 2004, assisted by funding from the City of Vancouver and from Friends of the Downtown Eastside,(5) the Carnegie Community Centre partnered with VMT to co-produce the first Downtown Eastside Heart of the City Festival: an annual twelve-day celebration of artists, art forms, cultural traditions, history, activism, people, and stories about the neighbourhood.

Out of the play’s deep taproot extended the festival’s wide, spreading roots. Its programs are developed by collaborative consensus with community partners and artists, some of whom partner with additional organizations for additional support. The most recent 2011 festival involved over 40 community partners, 30 venues, 100 events, and 1000-plus artists, from novices to cultural treasures.

As its roots extend, this tree of community arts practice grows taller and stronger, producing new flowers: smaller scale collaborative productions(6), mini-festivals around specific cultural communities, a national community play conference, leadership training institutes (7), creative partnerships with Runaway Moon and Jumblies Theatre, and professional co-productions incorporating job opportunities for community play participants. These projects and the funds they have drawn into the neighbourhood help us to give back to the community in the form of more creative opportunities.

Some flowers disseminated wild seed that have germinated into cross participation and new growth (8). Participants have gone on to create plays, concerts, exhibits, and history walks; to get more education, and jobs onstage, backstage, or teaching; to participate in arts or activism projects; and to sit on boards of non-profit organizations. The taller the tree, the deeper the roots it requires to stand firm in the torrents of life. Vancouver Moving Theatre collaborates with art and non-arts organizations in partnerships that intertwine our individual roots for cross-support, interconnection, and sharing of resources. We negotiate to codetermine goals, guiding principles, expectations, responsibilities, and in-kind contributions: this dance balances the needs of individuals, organizations, and the community as a whole.

Anyone can dig a hole and plant a seed. But as resident Bessie Lee said, “After one plants nice creative seeds in a field, they must be protected and nourished in order to provide a good harvest.” Each creative plant has its own development timeline, personality, and needs. A plant that grows too fast doesn’t develop strong roots to anchor it in place. And roots push down before leaves grow.

Artists are the leaves in our tree of community art practice, absorbing nourishment from the community as they co-create new art. Terry and I look for artists who are experts in what they do, enjoy working collaboratively, care about the project’s purpose, like the neighbourhood, support its values, and are ready to learn from it. We ask them to avoid taking sides on local issues in the rehearsal hall and to steer past negativity by sticking to arts and theatre protocol. In the words of director James Fagan Tait, as professional artists in a community-engaged process, “we have to be fully prepared at each rehearsal, to support and speak with respect to the cast members at every stage of the process, [and] to work out differences with members of the artistic team at another time and place without intruding on the rehearsal process.”

We ask the artists to help devise creative structures with room for community input, locally generated images, and opportunities to perform and build. We cast Anglo, Asian, Aboriginal, Latino and Black participants to honour our community’s demographics. We cast participants in roles and contexts to match talents and temperaments, and encourage them to work as a team to bypass blocks that stop the flow of expression and to move past preconceived limitations.

Ordinary individuals, when challenged and provided with opportunities and support, are capable of creating the extraordinary. Well organized, smoothly running, safe, fun, and inclusive environments encourage everyone—from novice to professional—to give of their best and to respect the work of others. Small everyday courtesies help big time on big projects. So do strategies that defuse tense situations in ways that leave everyone’s dignity intact and fresh, nutritious refreshments presented in a respectful manner. As artist Rosemary Georgeson reminds us “problems diminish by sharing and feasting.”

Within our limited resources, we provide fees for professional artists; honorariums for heavily involved community participants and performers; leadership training in exchange for in-kind service; mentoring, coaching, and skill-building opportunities for veteran play participants; participatory experiences for novices; limited involvement opportunities for community choirs and volunteers; refreshments, thank-you meals, and occasionally child care. When tough issues are involved, we have provided a peer counsellor with experience around these issues. We encourage social mixing; we don’t exclude people because of dress or everyday behaviour. Most events are free or by donation; we distribute complimentary or low-cost community tickets for ticketed events. We program street events during the Heart of the City Festival.

Working in “alliance” is a key principle in our strategy and survival as resident artists in the Downtown Eastside. Our work with social systems already in place is non-adversarial. We meet with artists and partnering organizations to learn how we can work with each other and what each can contribute, establishing with the lead artists a collaborative process that suits the community, the project, their working style, and the resources. We attach theme-related events to existing programs, and hire outreach workers who have lived and worked in the neighbourhood and understand its concerns. The art we co-create is about stories and images of this neighbourhood—a community that isn’t represented in mainstream art—incorporating aesthetic practices and forms outside the “high art” gates. And our documentation breaks out details of the collaborative process and contexts the community and its concerns. We try to never promise more than we can deliver.

Determining the scale of a project, its collaborative structure, artistic disciplines, balance of experimentation, and accessibility and community-engagement protocol is always an enormous challenge. So is nourishing artistic excellence and community process, giving value to each with funding, staffing, and resources. Too often, artists are overworked, productions need more rehearsal time and staff, and artistic visions are bigger than available resources. Not all affordable venues are wheel-chair accessible. Some places require front door security. Some people don’t like to go to certain neighbourhoods or venues. People can be on different “meds,” self-medicating, or in recovery. Some have personal hygiene or memory issues. Occasionally someone’s been too dangerous or disruptive to participate. If they’re verbally abusive, we move them out right away or others will be afraid. The challenge is to do this in a way that is respectful, does not humiliate, and leaves the person with the ability to come back at another time or in another context.

Before starting new projects we take time to learn how our partners’ community functions, its parts relate, and its connections act and interact. We co-design projects that suit their situation, values, and resources in order to develop meaningful relationships and work in support of each other, taking the time to learn and observe carefully before we act. The reason so many projects have been successfully realized and had a long-lasting impact is that everyone from professionals to novices worked hard and with mutual respect most of the time, coped respectfully with inevitable bumps, gave of their best, forgave mistakes, and really, really wanted the stories to be told and the projects to succeed. The resulting aesthetic is often raw, refined, and heart-felt. The successes are rooted in relationships of trust and cross-support developed over thirty years in a community Terry and I have come to love and respect. Learning from our mistakes, we take small steps in creating art that excites us, involves and engages people from our community, acknowledges our sources, and challenges negative stereotypes about the place we live.

We know that art offers no hard and fast solutions for the complexities of the human condition and its relationship to the lands and waters of this planet. Depending upon intention and context, art can empower, re-connect and heal or help displace, marginalize and scapegoat. We can’t control or stop the process of change, but we can make the best of our situations and advocate for healthier choices. In an unhealthy community, resources are used up faster than they can be replaced. Benefits are privatized and costs are born solely by the community. Loss of diversity results in vulnerability to change whether from scarcity or glut. A profoundly unequal world is profoundly out of balance—it is unsustainable.

An unhealthy arts practice is also unsustainable. Artists burn out. Self-care is essential when operating under conditions of unpredictability, stress, and overload. How do I cope? I alternate big and small projects. Do my homework in advance. Pay attention to what is said and done, prepared to adjust or abandon plans. When overwhelmed, I focus on one step at a time. If I can’t solve the problem immediately, I allow myself to postpone it. I preserve time for my family (especially suppers). I journal, sing, and go for long walks, taking big steps in the open air. I reach out to friends and colleagues I trust. I remind myself to plan as if I’m going to live forever and to live each moment as if I’m going to die tomorrow.

Nature’s systems teach us how to build healthy communities and a healthy community arts practice. Mature forests are resilient, healthy habitats, with aesthetic appeal and renewable resources. An old growth forest has many kinds of trees, young and old, growing together to ensure that diverse species will survive. This complexity of habitats nourishes opportunities to interact, providing a wealth of raw material to adapt to changing circumstances. Old growth forests bring energy into an area, preserve diversity, store resources to recycle into the system, reproduce without damaging or depleting the environment, and provide shelter and support for the next generation. Fallen decaying trees serve as nurse logs for new seedlings.(9)

Why do some communities vanish while others stay strong, why do some preserve their unique identities while others lose them? It is about inter-connection, roots, diversity, cross pollination, succession, balancing the needs of individuals and the community as a whole, preserving relationships. In the words of Downtown Eastside poet/activist Sandy Cameron, “We work to make our community a better place, not a perfect place, but a better place. If we look for immediate results in this work, we are in danger of falling into despair. Society doesn’t change quickly and our commitment is for the long haul.”(10) Our community’s stories help us draw strength from the past, to feel proud of our history and who we are, to have the courage to keep going and to never, ever lose hope.

As Terry and I enter our sixth decade of life, we think a lot about transferring information and passing on the torch. Even when a tree falls, it is only halfway through life. It continues to have the capacity to shelter, to nourish the earth with nutrients as it decays, leaving its legacy: a seedbed for new creation. Whether or not we successfully pass a sustainable festival onto a new director, we are working on written and audiovisual legacies to serve as creative seed to nourish new generations of artists. We are exploring with community partners opportunities for a more deeply rooted sustainability for Downtown Eastside arts than gambling upon gaming and the largesse of corporations.

Our trees of community art practice—the culture we carry, the art we create—show how we can come together despite seeming differences to reverse collective forgetting so communities see themselves clearly reflected in their own light, rather than through the distorted images of other people’s mirrors. In rediscovering healthy aspects of our home and culture, all of us recover a sense of ownership, pride, and destiny; motivation to protect our communities; and wisdom to preserve them for future generations. You cannot leave it to other people to take care of your community.

“It’s the people who make our community beautiful,” said poet Sandy Cameron, “and they do it be reaching out to each other and helping each other. Even as the giant fir is nurtured by its roots, so our community of the Downtown Eastside is nurtured by its members." (11)

Guiding Principles of VMT’s Tree of Community Art Practice

- Involve culturally diverse professional artists engaging in their art practice with a community;

- Create art from inception through completion with, by, and for that community;

- Partner artists and arts organizations with non-art organizations;

- Build projects of all sizes and shapes, from performing to visual arts, media arts, processions, and community celebrations;

- Support community members with a variety of art-making and capacity-building opportunities;

- Integrate art making with a community’s stories and concerns, images and traditions, assets and hopes;

- Intertwine process and product—all part of the art; Cultivate respectful, inclusive environments;

- Encourage everybody involved—from novice to master—to give of their best;

- Relate to the whole community, including Aboriginal, Asian, and Anglo;

- Result in a transformative experience;

- Leave a legacy for the future.

NOTES

1 Acceptance speech on behalf of the Honourable Jim Green by former city planner Nathan Edelson to the Planning Institute of BC, 5 November 2011.

2 See my article, “

Excavating Yesterday: The Birth, Growth and Evolution of a Resident Artist in the Downtown Eastside,” alt.theatre 7.2 (2009): 24-28.

3 The community play form was brought to Ontario by Dale Hamilton (1990) who inspired Cathy Stubington to create a community play in Enderby, BC (1998), in turn inspiring the Downtown Eastside. See Ann Jellicoe, Community Plays: How to Put Them On (Methuen, 1987).

4 See my article, “

The Downtown Eastside Community Play,” alt.theatre 3.4 (2005): 12-15.

5 Friends of the Downtown Eastside is a group of business leaders supportive of grass roots community-led renewal in the Downtown Eastside

6 See, for example, my article, “

We’re All in This Together: Negotiating Collaborative Creation in a Play About Addiction,” alt. theatre 5.4 (2008): 14-20.

7 See my dispatch, “

Reflections on a cross-country collaboration in community arts training,” alt.theatre 7.3 (2010): 31.

8 See Leath Harris, “The Magic Circle,” alt. theatre 4.1 (2006): 9-10, 15.

9 Toronto’s Jumblies Theatre acts as a giant nursing log for new trees of community art practice with its generous and visionary start-up support of resources, knowledge, mentoring, and interning.

10 Sandy Cameron, “Longing for Light,” Carnegie Newsletter, 15 July 2009.

11 Sandy Cameron, “Dear Friends, Thank You,” Carnegie Newsletter, 4 August 2010.

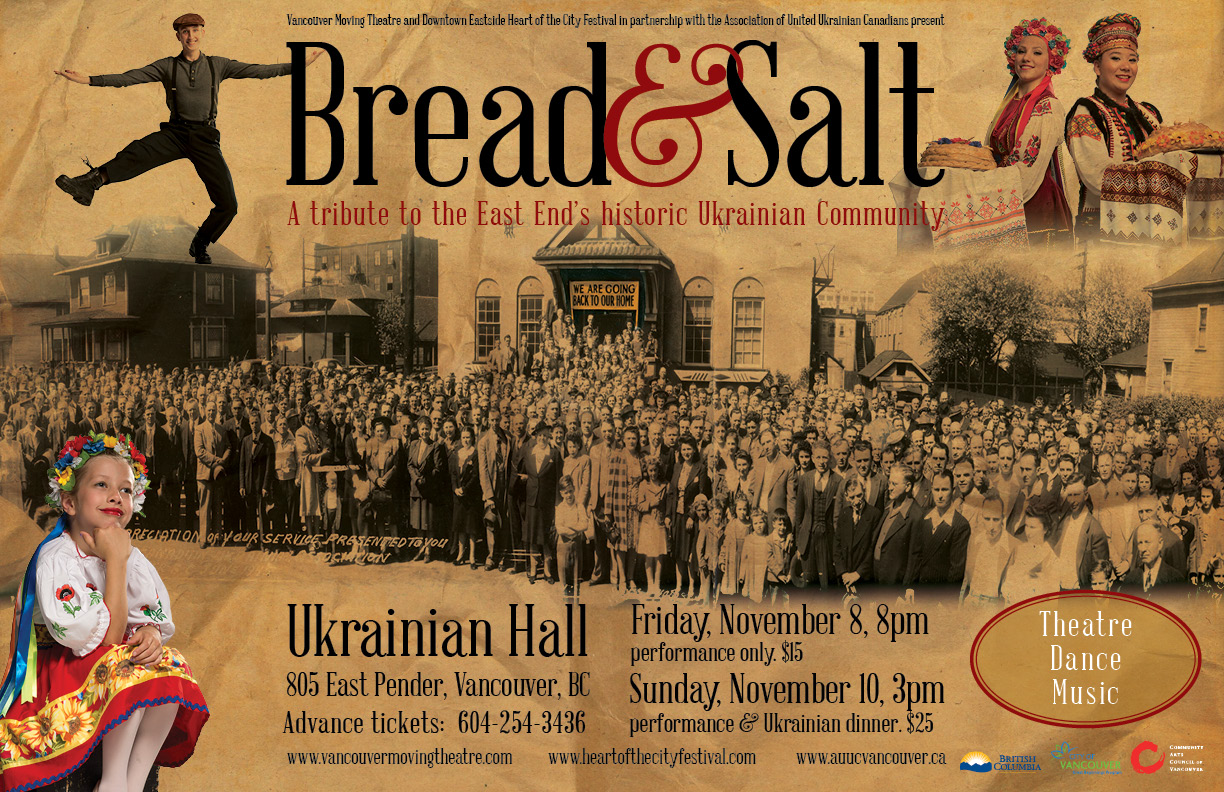

Inspired by stories and memories from the East End’s historic Ukrainian community, this 85th Anniversary tribute interweaves oral history with live theatre and music, haunting choral singing and the driving rhythms of Ukrainian dance.

Bread and Salt is performed by a multi-generational cast of over sixty professional and community actors, singers, dancers and musicians.

Co-writers - Beverly Dobrinsky and Savannah Walling

with writings by Clifford Odets, Helen Potrebenko, Ivan Franko and Taras Shevchenko

Director - James Fagan Tait*

Music Director - Beverly Dobrinsky

Actors - Montana Hunter, Stephen Maddock*, Billy Marchenski, Helen Volkow

Musicians - Sheila Allen, Jonathan Bernard, Alex Chisholm, Mark Haney, Alison Jenkins, Bud and Heidi Kurz

Conductors - Gregory Johnson and Beverly Dobrinsky

Dance Directors - Debbie (Wishinki) Karras and Laurel (Parasiuk) Lawry

Stage Manager - Leigh Kerr*

With the Vancouver Folk Orchestra, Barvinok Choir, Dovbush Dancers the AUUC School of Dance.

Choreographic contributions by Serguei Makarov, Liliya Chernous, Gina Alpen (Con8 Collective) and Danya Karras.

*appearing courtesy of Canadian Actors Equity Association

Click here for more information and the history of the Ukrainian Hall.

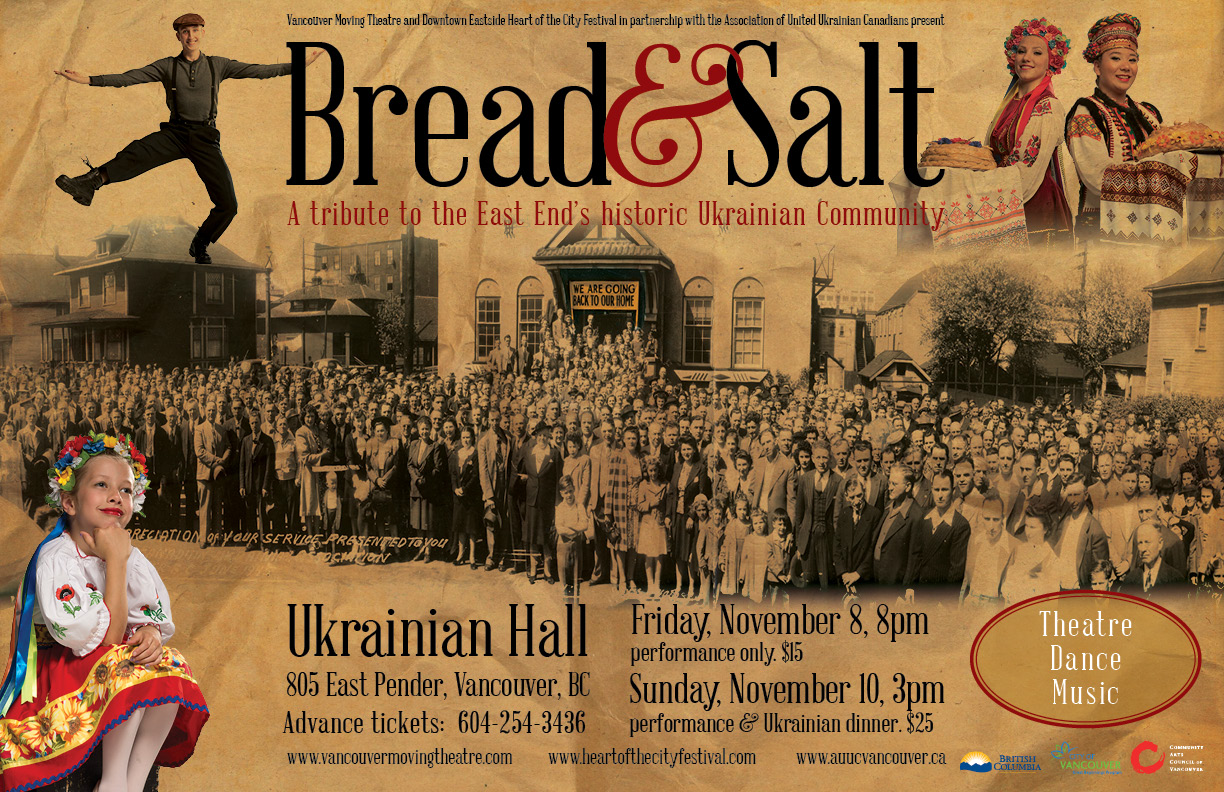

Inspired by stories and memories from the East End’s historic Ukrainian community, this 85th Anniversary tribute interweaves oral history with live theatre and music, haunting choral singing and the driving rhythms of Ukrainian dance.

Bread and Salt is performed by a multi-generational cast of over sixty professional and community actors, singers, dancers and musicians.

Co-writers - Beverly Dobrinsky and Savannah Walling

with writings by Clifford Odets, Helen Potrebenko, Ivan Franko and Taras Shevchenko

Director - James Fagan Tait*

Music Director - Beverly Dobrinsky

Actors - Montana Hunter, Stephen Maddock*, Billy Marchenski, Helen Volkow

Musicians - Sheila Allen, Jonathan Bernard, Alex Chisholm, Mark Haney, Alison Jenkins, Bud and Heidi Kurz

Conductors - Gregory Johnson and Beverly Dobrinsky

Dance Directors - Debbie (Wishinki) Karras and Laurel (Parasiuk) Lawry

Stage Manager - Leigh Kerr*

With the Vancouver Folk Orchestra, Barvinok Choir, Dovbush Dancers the AUUC School of Dance.

Choreographic contributions by Serguei Makarov, Liliya Chernous, Gina Alpen (Con8 Collective) and Danya Karras.

*appearing courtesy of Canadian Actors Equity Association

Click here for more information and the history of the Ukrainian Hall.  Inspired by stories and memories from the East End’s historic Ukrainian community, this 85th Anniversary tribute interweaves oral history with live theatre and music, haunting choral singing and the driving rhythms of Ukrainian dance.

Bread and Salt is performed by a multi-generational cast of over sixty professional and community actors, singers, dancers and musicians.

Co-writers - Beverly Dobrinsky and Savannah Walling

with writings by Clifford Odets, Helen Potrebenko, Ivan Franko and Taras Shevchenko

Director - James Fagan Tait*

Music Director - Beverly Dobrinsky

Actors - Montana Hunter, Stephen Maddock*, Billy Marchenski, Helen Volkow

Musicians - Sheila Allen, Jonathan Bernard, Alex Chisholm, Mark Haney, Alison Jenkins, Bud and Heidi Kurz

Conductors - Gregory Johnson and Beverly Dobrinsky

Dance Directors - Debbie (Wishinki) Karras and Laurel (Parasiuk) Lawry

Stage Manager - Leigh Kerr*

With the Vancouver Folk Orchestra, Barvinok Choir, Dovbush Dancers the AUUC School of Dance.

Choreographic contributions by Serguei Makarov, Liliya Chernous, Gina Alpen (Con8 Collective) and Danya Karras.

*appearing courtesy of Canadian Actors Equity Association

Click here for more information and the history of the Ukrainian Hall.

Inspired by stories and memories from the East End’s historic Ukrainian community, this 85th Anniversary tribute interweaves oral history with live theatre and music, haunting choral singing and the driving rhythms of Ukrainian dance.

Bread and Salt is performed by a multi-generational cast of over sixty professional and community actors, singers, dancers and musicians.

Co-writers - Beverly Dobrinsky and Savannah Walling

with writings by Clifford Odets, Helen Potrebenko, Ivan Franko and Taras Shevchenko

Director - James Fagan Tait*

Music Director - Beverly Dobrinsky

Actors - Montana Hunter, Stephen Maddock*, Billy Marchenski, Helen Volkow

Musicians - Sheila Allen, Jonathan Bernard, Alex Chisholm, Mark Haney, Alison Jenkins, Bud and Heidi Kurz

Conductors - Gregory Johnson and Beverly Dobrinsky

Dance Directors - Debbie (Wishinki) Karras and Laurel (Parasiuk) Lawry

Stage Manager - Leigh Kerr*

With the Vancouver Folk Orchestra, Barvinok Choir, Dovbush Dancers the AUUC School of Dance.

Choreographic contributions by Serguei Makarov, Liliya Chernous, Gina Alpen (Con8 Collective) and Danya Karras.

*appearing courtesy of Canadian Actors Equity Association

Click here for more information and the history of the Ukrainian Hall.

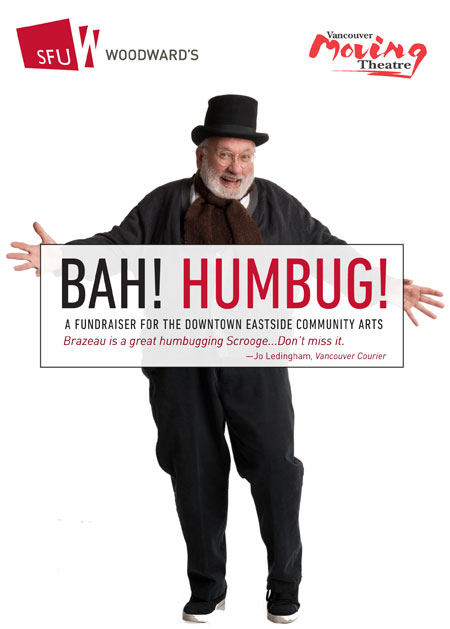

A witty, heart-filled production!

–Megan Harris

A fantastic way to get into the spirit of the season!

–Diane Roberts, urban ink

.. one sweet humbug... becoming an annual favourite... a made-in-Vancouver Christmas Carol... Brazeau is a great humbugging Scrooge...Don't miss it.....

-Jo Ledingham, Vancouver Courier

A witty, heart-filled production!

–Megan Harris

A fantastic way to get into the spirit of the season!

–Diane Roberts, urban ink

.. one sweet humbug... becoming an annual favourite... a made-in-Vancouver Christmas Carol... Brazeau is a great humbugging Scrooge...Don't miss it.....

-Jo Ledingham, Vancouver Courier