Originally published in alt.theatre vol. 10.4 (Summer 2013)

Download a PDF version of this article

By Rosemary Georgeson with Savannah Walling

As theatre artists involved in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside in British Columbia, we—Rosemary Georgeson and Savannah Walling—have been friends for over ten years and have collaborated on various projects together. We’ve also spent a great deal of time sharing with each other about other projects we’ve had on-the-go in rural and urban communities, bringing together what we’ve learned through our mistakes and discoveries, our successes and our practices. We’ve thought that this dialogue—which evolved through our conversations and relationship—would be of interest and relevant to our larger arts community.

Rose

As a fifty-five-year-old First Nations woman, it is only in my lifetime that we as First Nations people have been accepted in theatres and presenting houses. We could perform but we were never audience members. My culture has always had its own theatre and forms of community arts, but the Canadian government shut them down from the 1880s to 1951. Although many of our cultural traditions continued underground, our voices are only coming fully back into the public now. Just that knowledge of this legacy explains the need for creating relationships inside First Nations territory that you are situated or entering.

Years ago I was at an arts conference participating in a workshop on how to engage First Nation communities in the arts. I heard a theatre producer speak about going into a Northern community with his show and how much effort and money he put into getting his show there. He was very angry that no one even made an attempt to come out for his production. When I asked about his outreach process, he had no response and seemed irritated that I would ask that question. He did say that when he mounted a production anywhere else, he didn’t need to do outreach—he had PR people to do that for him. He made it quite clear, though, that he would never again attempt to take a production into a First Nations community. This was a turning point for me, hearing him speak this way about First Nation people and the arts. It was through the encounter with this gentleman that I started looking at the need to develop and build lasting relationships within our communities and between communities.

Savannah

As a sixty-seven-year-old mostly Anglo immigrant from the US whose ancestors fought on both sides of the Revolutionary, Civil, and Indian wars, I’ve seen big changes over the years in relations between non-First Nation and First Nation people. When I was born, Aboriginal/First Nations people were commonly called “Indians.” Indians in Canada were forbidden to vote, buy land, practise their cultural customs, or hire lawyers to pursue land claims. Men lost their Indian status if they joined the Canadian military. Most Indian children were taken from their families and sent to residential school. I was taught at public school—where there was usually not an Indian in sight—that Indians were a dying culture and Indian people would soon be assimilated. Today however, the old government restrictions have been lifted. According to the 2006 Canadian Census, the Aboriginal population is growing faster than the general population. Because of the amount of unfinished treaty business in B.C., treaty negotiations with First Nations are ongoing. Due to a history of broken trust between First Nations and immigrant communities, building relationships is foundational. Three Coast Salish Nations are embedded within and around the City of Vancouver where I live and work. Today’s world is a very different world than that of my childhood. As a result, just about the most important step of my training and practice as an artist has involved learning to negotiate relationships with First Nation community partners, artistic colleagues, and community participants.

Every community and every individual is unique. No single approach suits every situation.

Rose

Relationship building is an ongoing process that does not happen overnight, but it is an essential key to opening doors to make a community arts project all-inclusive and to building relationships with First Nations communities. This applies to all aspects of interaction within our communities. Entering into a new community arts project is always a challenge. It takes time to build relationships and to ensure that your project is all inclusive. Building trust is so important. Take the time to go out and meet the people you want to connect with. We First Nations people have centuries of experience of our stories and ways being misappropriated—just taken and misconstrued into what non-First Nations thought they should be. This makes for bad feelings and mistrust when others enter into our communities.

Savannah

I’ve made some serious blunders on creative journeys involving First Nations cultural content and collaboration: mistakes due to ignorance, inexperience, cultural misunderstanding, working too fast and not putting in the time needed to build relationships. So I’ve done a lot of learning the hard way. As a result, some projects never made it to completion. A couple of others almost foundered, but instead of giving up, we interpreted the obstacles as a signal to take more time—and that was what was needed. The most important principle I’ve learned is that respect is the foundation of relationships.

Rose

While working for urban ink productions a few years ago in Williams Lake on the Squaw Hall community arts project1— and after making a few mistakes there—our team realized that we needed to have people from the community to help us find our way. As we were merging deeper into the community and getting to know more people, we started to talk with them about forming an advisory committee. The idea was met with appreciation and relief: We were asking them to become more deeply involved in our project and the community would have a much stronger voice regarding the work created. The committee was such a great resource for finding how we could best serve Williams Lake and the surrounding Nations and honour the stories they were sharing with us. Our committee was made up of people from that territory, First Nation and non-First Nation peoples, and men and women from all sectors of the community—from Aboriginal educators and a chief to a First Nations liaison for the health department, a city councillor, a reporter/author/historian for the local newspaper, and local businesspeople.

Savannah

Over the years, I’ve come to appreciate that engaging with First Nation communities means engaging with values and ways of life that are distinct from Canada’s immigrant-based cultures. In practice this has meant occasionally reminding production stage managers that body language and everyday cultural interactions can differ. Some First Nations individuals will avoid eye contact as a sign of respect. Many non-First Nations people in strange, stressful situations learn to react with a lot of activity and conversation until they restructure the situation or extricate themselves from it. Many Indigenous people, on the other hand, when put into the same situation may remain motionless and watch until they figure out what is expected. Stage managers unfamiliar with cultural differences can interpret these responses as indicating lack of interest or trustworthiness. When looking for a stage manager for the Storyweaving project2 we kept in mind that First Nations culture has traditionally relied on an ethic of non-interference and voluntary cooperation. We looked for someone who was willing to learn about Aboriginal culture and traditional ways of demonstrating respect, and who was prepared to do their best to operate by the longhouse philosophy, relying on example and persuasion rather than authority and force.

We reschedule and do “work-arounds” when we run into the kinds of situations some people call “Indian time”: unexpected delays relating to “the time things take to happen,” or “the time it takes to do things in a good way and when the time is right.” Delays also can happen when ceremonial events are happening simultaneously with the projects: the reality is that Indigenous participants and cultural leaders may have different priorities than those of the non-Indigenous artistic team, regardless of the project’s artistic interest and their commitment to it.

We’ve also learned not to make assumptions about what Aboriginal culture is and what its customs may be. Every community and every individual is unique. No single approach suits every situation. Some Aboriginal people don’t know their own culture and language, which is due to the impact of residential schools and assimilation processes forced upon First Nation people. Some people are negotiating the tough challenge of “walking in two worlds simultaneously”: the world of the ancestors and the urban world of today. And some people are knowledge-carriers of their culture.

Projects can have consequences that are sometimes bad and sometimes good. By staying in contact with a community after the project is completed, you show your willingness to be accountable— and to stay in relationship.

Rose

Do your research, look at the history and accomplishments, and find out some of the challenges that are faced in our indigenous communities and the existing communities around us. Look at interactions and relations between First Nation communities and neighbouring non-First Nation communities. This will tell you a lot about what you will encounter. So will listening to what a community is telling you. Don’t be afraid to do your research and find key people who can guide you to finding the right parties to speak with. Other important keys to success are being able to fully explain your project, asking permission to bring it into their communities, and finding out how they would like to be involved. Always consult with people and partners in the community regarding storyline and changes to your project. Ensuring that our ways and traditions are respected honours our communities in a healthy way. Being open and honest is so important—about where our stories will go and how they will be kept intact and brought back to a community.

Savannah

The following are some steps that can help in negotiating collaboration with First Nation communities. Many are eloquently described in a great web site dedicated to helping journalists tell Indigenous news stories. Reporting on Indigenous Communities (www.riic.ca) is created and curated by CBC reporter Duncan McCue who is Anishinaabe and an adjunct professor of the UBC School of Journalism:

- If you are planning a project on First Nation traditional territory, obtain permission from the tribal council, cultural centre, or organization involved from the cultural territory you are entering;

- Ask the person with whom you are setting up a meeting to help you—before you arrive—with the proper greetings and traditional territorial protocol;

- Acknowledge the host community, its people, and territory at the beginning of meetings;

- It helps if you have a trusted advisor or cultural translator to help you negotiate the local customs and help you locate people who have the authority to give permissions;

- When you’re uncertain about the customs and don’t know what to do, ask your host—and when all else fails, follow the lead of those around you;

- If someone pours you a cup of tea, take time to drink it, because refusing food or drink from your host may be seen as disrespectful;

- Take time to develop respectful relationships with the elders, who are carriers of history and cultural teachings; be prepared to offer a gift that respects their time and commitment to the project and always let them finish what they are saying;

- Take time to learn who has ownership or stewardship over the songs, dances, images, and other material, and who has the authority to give permission for their use and under what circumstances;

- Learn the culturally appropriate ways to represent and publicly share knowledge and learn the limits of the permission;

- It is not always easy to learn who has the authority to give permission and under what circumstances—it means investing time and patience;

- Always request permission before filming cultural material, and if you agree not to record it, point your camera in another direction so people know it isn’t running;

- Sometimes anger or frustration will be directed your way or you will become the recipient of five hundred years of anger: take a deep breath, listen, conduct yourself with respect, and move on your way;

- Keep a good sense of humour—most of all about yourself.

Jo-ann Archibald has written an important book called Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body and Spirit (2008). She is from the Stó:l Nation and is an associate dean for indigenous education in the Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia. She talks about how the responsible use and ownership of stories can be complex and difficult to carry out, with the process influenced by considerations ranging from the personal and familial to the community and political. Each nation has its own traditions around how stories may be told for teaching or learning purposes. Some may be owned by individuals or clans, some may be in the public domain, some can only be told at certain times of the year or at certain events, some can be told only in part. Your responsibility as collaborating artists is to learn about and respect the traditional cultural ways of teaching, learning, sharing, and presenting knowledge. Proper acknowledgement of the source material is part of using knowledge responsibly.

Once a story or other cultural material is shared, you incur reciprocal obligations: to do your best to make sure that what you present is balanced and truthful, that it is presented in a way that is culturally appropriate, that you will try to protect people from any negative impact that might result from public sharing, and that the people who assisted you get to see, read, or hear their story. Offer them transcripts of the interviews, opportunities to participate or give feedback, and tickets to the performances.

Projects can have consequences that are sometimes bad and sometimes good. By staying in contact with a community after the project is completed, you show your willingness to be accountable—and to stay in relationship.

Rose

I have been doing this work for the past twelve years with Vancouver Moving Theatre3 and urban ink productions. I’ve seen first-hand the impact of building relationships in a community where First Nation people have been heard and their stories honoured—just being recognized as first peoples of that territory. It is the interaction between First Nation people and other cultures—with both parties learning new things and being heard and respected—that creates change and makes room for everyone. When the time is taken to build these relationships, you see relationships shifting between First Nation and non-First Nation communities.

Savannah

Vancouver Moving Theatre’s practice has been profoundly informed by the insights of friends and cultural advisors (including Joann Kealiinohomoku, Terrell Piechowski, and Alta Begay), by our years of collaboration and consultation with Aboriginal colleagues Rose Georgeson and Renae Morriseau, and by insights of many Aboriginal community participants, artistic colleagues, and cultural teachers. We are deeply in their debt.

Rose

When I first came into contact with Vancouver Moving Theatre just over ten years ago, they had a relationship with the Downtown Eastside built over years of being part of the community. I came on as Aboriginal outreach worker for The Downtown Eastside Community Play. It was my first time working in “outreach.” I learned so very much from that experience that I carry into all my “relationship-building gigs.” My listening skills have become much more attuned and I have learned a deeper level of patience as I have found trying to rush things does not benefit anyone or the project.

I’ve also realized how much I understand from my traditions about “community” and building positive relationships with a lasting impact. Respecting and recognizing all individuals is very important in Vancouver Moving Theatre’s practice and what they bring to their community. Over the past ten years, as I have been involved in different projects with the company, I see First Nations faces I first saw ten years ago when I was sitting in the audience of the Downtown Eastside Community Play, apprehensive about the First Nations content we were sharing and how it was shared. Many of those same faces are now involved as participants and loyal followers of Vancouver Moving Theatre. When working on the Storyweaving project I was struck by seeing so many friends who were there ten years ago in the beginning, and how we have all grown over the years due to the diligence of Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling of Vancouver Moving Theatre and their passion and devotion to building and keeping relationships they have built over the years. The Storyweaving project revealed the fruits of over ten years of relationship building and its positive impact. Playing to a packed house every night, supported by not only First Nation people but by everyone who attended the show, was proof we can learn from our mistakes, from each other, through listening to needs, and, last of all, by taking time to build these relationships, honouring and respecting the people that help bring this art form to light.

Rose and Savannah

Like all living creatures we make mistakes, we learn from those mistakes and never know what can grow from them. That is so often the case as you enter into new territories and new communities when engaging in community arts. But it is what you learn and create from these mistakes that is the true beauty.

NOTES

- The Squaw Hall Project (2009-2010) was a community-engaged theatre project produced by Twin Fish Theatre (Nelson) and urban ink productions (Vancouver) working with Youth and Elders from the Secwepemc, Carrier,Tsilhqot’in communities. It culminated in an original play (Damned If You Do; What If You Don’t) and short film (A Community Remembers), which presented on tour to local band communities and at the DTES Heart of theCity Festival in Vancouver, 2011.

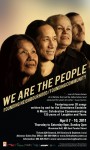

- Storyweaving, an original theatrical production honouring First Nations ancestral and urban presence in Vancouver, was produced May 11-20, 2012, by Vancouver Moving Theatre/Downtown Eastside Heart of the City Festival in a partnership with the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre—with educational and spiritual support from the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

- Vancouver Moving Theatre is a Downtown Eastside-based professional arts organization co-founded by executive director Terry Hunter and artistic director Savannah Walling